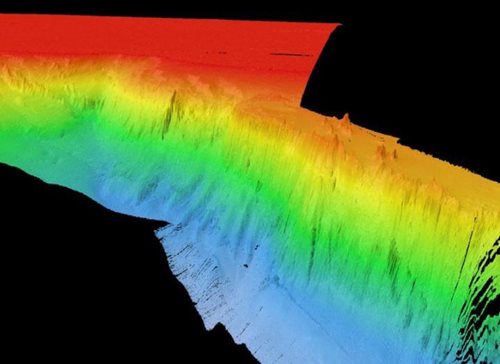

The Porcupine Bank Canyon showing several-hundred-metre-high cliffs. Image: UCC

The Porcupine Bank Canyon showing several-hundred-metre-high cliffs. Image: UCC

With nearly all of the world’s landmasses mapped in minute detail by orbiting satellites, the planet’s vast oceans remain the last place for intrepid explorers to dive into the unknown.

To that end, a team of scientists led by University College Cork (UCC) jumped on board the RV Celtic Explorer to explore the edge of Ireland’s continental shelf. Located 320km west of Dingle, the team set about mapping an area twice the size of Malta.

There, they came across an enormous submarine canyon system – called the Porcupine Bank Canyon – with near-vertical 700 metre-high cliffs in places and murky depths reaching as far down as 3km.

To put this into perspective, this would be the equivalent of 10 Eiffel Towers stacked on top of one another.

Importance to our planet

The discovery is significant for a number of reasons. Most notably, it helps us better understand how submarine canyons transport carbon to the deep ocean.

Covering approximately 70pc of our planet’s surface, oceans are vital in reducing excess CO2 from the atmosphere, absorbing it at the surface with these canyons pumping it to where it cannot escape.

The Porcupine Bank Canyon is the westernmost canyon on the Irish continental shelf. Its upper canyon is filled with cold water corals and mounds which create a 28km-long rim on the lip of the canyon.

Diving deeper into the canyon using its Holland I submersible, the team found significant build-up of coral debris that has fallen from hundreds of metres above.

Feeling the pulse of the Atlantic

“This is all about transporting carbon-stored cold water corals into the deep. The corals get their carbon from dead plankton raining down from the ocean surface – so, ultimately, from our atmosphere,” said Prof Andy Wheeler of UCC and the Irish Centre for Research in Applied Geosciences (iCRAG).

“Increasing CO2 concentrations in our atmosphere are causing our extreme weather; oceans absorb this CO2 and canyons are a rapid route for pumping it into the deep ocean where it is safely stored away.”

The new detailed maps released by the team show lobes of sediment debris and the scars from submarine slides as the canyon walls collapse.

There is also exposure of old crustal bedrock and incised channels in the canyon floor carved by sediment avalanches.

Speaking of the research, Dr Aaron Lim, who led the expedition, said: “So far from land, this canyon is a natural laboratory from which we feel the pulse of the changing Atlantic.”

Colm Gorey

This article originally appeared on www.siliconrepublic.com and can be found at:

https://www.siliconrepublic.com/innovation/gigantic-canyon-irish-continental-shelf-images